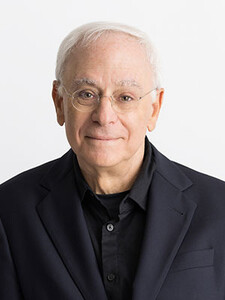

In Long-Awaited Volume, Professor Robert Post Tells Story of Taft Court in its Own Time

After 35 years and 1,608 pages, Sterling Professor of Law Robert C. Post ’77 has written the definitive history of the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice William Howard Taft.

The Taft Court: Making Law for a Divided Nation, 1921–1930 (Cambridge University Press) is the long-awaited 10th volume of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States. The series, supported by funds left to the United States government by Oliver Wendell Holmes and supervised by an editor appointed by the president, has, in Post’s words “a long, distinguished, and troubled history.” Post’s volume was originally assigned in 1955 to Yale Professor Alexander Bickel, who died before writing it. It was then assigned to Yale Professor Robert Cover, who also died before completing a draft. Post began work on the Taft volume in 1988.

Post writes in the book’s preface that he sought both to produce a thematic, monographic account of the Court, and yet also to produce a “history of record.” Post seeks to demonstrate how the Court’s work was in continual dialogue with prominent cultural themes and conflicts of the 1920s. “As a form of human action, law cannot be reduced to abstract theory or prescription,” Post writes. “It is made in the rich complexity of historical time.”

WATCH: Post discusses the book with the National Constitution Center

And what a time it was. In 1920, voters elected Warren G. Harding president on a platform of returning the country to normalcy after the massive changes produced by the first World War.

But this was not a simple matter. “Jazz, flappers, radio, and cars burst onto the scene,” Post writes. “Yet so did Prohibition, fundamentalism, the KKK, and 100 percent Americanism.” In the 1920s, Americans sought both to resurrect old pieties and vigorously to pursue brave new innovations.

Harding appointed four new Justices in less than 18 months. He conceived the Court as an instrument for returning the country to antebellum principles. Foremost among these were the restoration of the constitutional values of substantive due process and federalism. During World War I, the Wilson administration had seized control over the nation’s railroads and telegraph systems. It imposed price controls over almost all consumer goods to reorient the economy to the production of wartime materials. It recognized unions and created a national labor policy. It suspended antitrust regulations. The federal government exercised more detailed economic control than ever before or since.

Wilson’s wartime policies were considered both terrifying and necessary. They opened new possibilities that were attractive and yet profoundly disorienting. “The Taft Court was charged with the thankless task of constructing law for a society that was deeply confused about what it wanted,” Post writes. Thus the Taft Court sustained the Transportation Act of 1920, which converted the ICC into the governor of virtually all railroads, both interstate and intrastate, and yet it struck down the Child Labor Tax Act.

In an effort to restore antebellum values, the Taft Court revived the doctrine of Lochner v. New York, which put the burden of justifying social and economic regulation squarely on the government. The Court’s doctrinal innovations were so severe that they would lead directly to the crisis of the New Deal during the next decade.

The Taft Court has received acclaim from leading legal scholars and historians. Anthony Kronman ’75, Sterling Professor Law at Yale Law School, wrote, “Robert Post’s long-awaited history of the Taft Court is a masterpiece — a work for the ages. It is infused with great humanity, enriched by astonishing erudition, and marked throughout by a high philosophical intelligence that never loses sight of the great questions and deep tensions of this remarkable period in American life.”

Howard Gillman, Chancellor of the University of California, Irvine, wrote that Post “has produced an extraordinary account of the final decade of pre-New Deal constitutionalism and the birth of the modern Supreme Court.”

Post’s book contains biographical chapters on the individual Justices of the Court, including major studies of Taft, Holmes, Brandeis, and Stone. But Post also discusses the Court’s responses to social and economic legislation, Prohibition, federalism, labor, and race.

The 1920s were a period of intense polarization in the United States. Labor conflict was so fierce that the American Federation of Labor called for the restriction of federal equitable jurisdiction and the repudiation of judicial review. Conflict over Prohibition was so intense that 1920 was the one and only time in the nation’s history that Congress did not reapportion itself based upon the census, because it was feared that the expanding urban population would undermine the Volstead Act.

In this environment, the challenge facing the Taft Court was how to announce law that would be received as legitimate and not merely partisan. Members of the Court adopted four basic strategies. The first was to ground constitutional law in history and tradition. This had been the basis of conservative jurisprudence since the 1890s, and it was most consistently and eloquently articulated during the 1920s by James C. McReynolds. This view of constitutional jurisprudence equated the Court’s authority with that of a common law court, which could speak for “public sentiment . . . crystallized in general custom.”

The second was Holmesian positivism, which conceptualized America as agonistic rather than united by common customs and traditions. Legislatures, not courts, offered the only authoritative voice of society, because legislatures were the only institution that allowed for orderly processes of change in the face of existential conflicts among social actors. Only legislatures could express the “dominant opinion” of a society. Those defending Prohibition’s fiercely controversial suppression of the nation’s drinking mores found much support in Holmes’s jurisprudence of positivism, which has since become the intellectual foundation for the modern administrative state.

A third strategy, exemplified by Taft himself, was to identify law with the prerequisites of prosperity. Justices like Taft and Sutherland believed that Americans were united by a comprehensive desire for an expanding economy. This desire was more fundamental than any “mere product of popular will” that might be issued by a legislature. The Court’s primary task, therefore, was to protect the property rights that facilitated economic growth.

A fourth strategy, which was held by Brandeis alone, was to imagine American constitutional law as grounded in the project of democracy. For this reason, the political requirements of self-governance were to be given priority over the economic requirements of property.

The book also discusses Taft’s innovative reconstruction of the position of Chief Justice. Taft made the Chief Justiceship into a position that was closer to an English Lord Chancellor than it was to the role of any previous American judge. Taft, the only person in American history ever to head both the Article II and Article III branches of government, reconstructed the federal judiciary into a coherent branch of government. He transformed the Supreme Court from a final appellate tribunal into what contemporaries called a “ministry of justice” by vastly expanding its discretionary jurisdiction. He constructed the modern Supreme Court building. He was an unapologetic political actor, frequently consulting with presidents and lobbying Congress.

Post describes Taft as literally working himself to death. He died just weeks after leaving the Court in 1930. But Taft wrote that the appointment to the Court was his greatest honor: “I don’t remember that I ever was President.”